News & Articles

Modern Rational Empiricism: A Thinking Model

Modified a bit From The Muscle System Consortia (MSC) Course: “Manual Muscle Testing” – Art and Science: An Exploration of its History, Physics/Mechanics, and Utility in Practice 2016

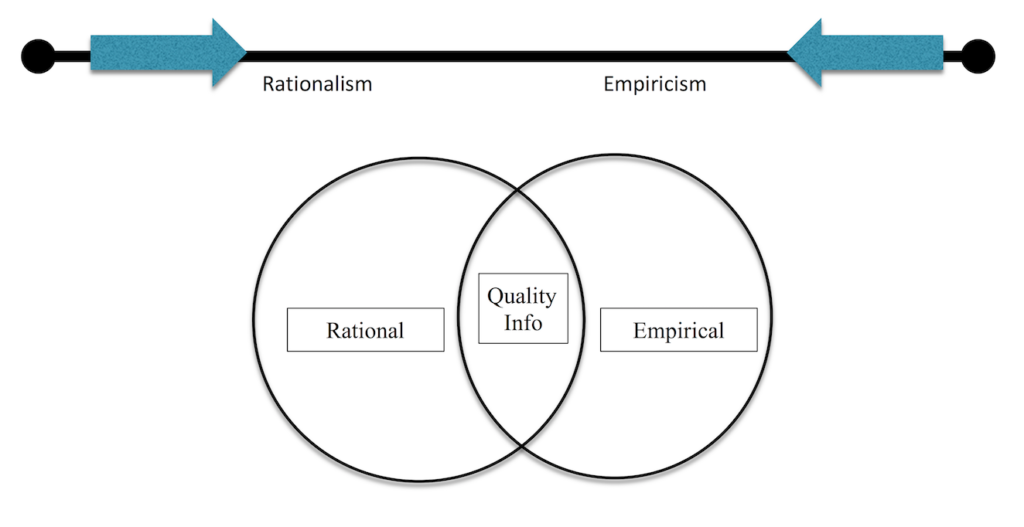

The MSC embraces the notions of Modern Rational Empiricism as a guide in processing, generating, and interpreting information regarding the skeletal muscle system. As an information assessment model, it will serve to establish the quality of any information used by and presented through the MSC Spheres. The model is used in order to answer questions like:

What gives us the basis for qualifying claims of fact?

What determines the quality of information?

What qualifies as support?

What constitutes as evidence?

What is the information’s utility in making decisions, judgments, or testing claims?

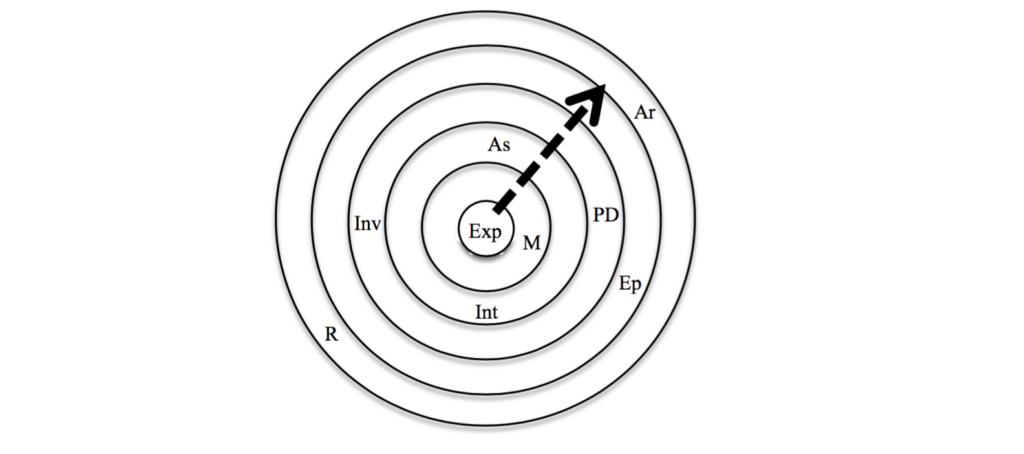

The MSC contends that it is the dynamic and balanced interplay of the following elements of human thinking and behavior that construct the Philosophy and resulting Methodologies of Modern Rational Empiricism: Experience, Memory, Intuition, Association, Pattern Discernment, Invention, Experimentation, Reason, and Argumentation. Each element contributes to the generating, processing, and interpreting of information for human purposes. Information gleaned from only a single element is limited in its ability to generate high quality information. Modern Rational Empiricism demands the interaction of these elements to establish information quality.

Here is a diagrammatic representation of the generally progressive nature of accumulating and using the main categories of information gathering and process that constitutes Modern Rational Empiricism as a thinking and decision making model: Exp = Individual Experience, M = Memory, Int = Intuition, As = Association, PD = Pattern Discernment, Inv = Invention, Ep = Experimentation, R = Reason, Ar = Argumentation

Define each element, its limits, and its partners/relationship to the other elements.

1. Experience (n.) (Empirical – generating)

Experience serves as a cornerstone to Modern Rational Empiricism. Experience provides the raw data that facilitates thinking and behavior. Given its special status it is necessary to establish a baseline of description and understanding of Experience as a unique element and to contextualize it within Modern Rational Empiricism. As necessary and foundational as experience is to “being” human, and generating information, there are issues with the utility of the information that comes only from individual experience. The information that comes from individual experience is always limited by, and to, the environments and conditions that individuals find themselves in. As there are potentially an infinite number of environments and conditions one could possibly experience no individual experience can be all encompassing. Yet, in light of critical thinking, decision-making, and making judgments, where there are limitations on quantitative observation, an individual is often found to be relying on their own unique and limited experience. One must acknowledge these limitations and recognize both the strength and weakness of experience-only information.

Definition

“practical contact with and observation of facts or events.”

“the knowledge or skill acquired by such means over a period of time, esp. that gained in a particular profession by someone at work.

“an event or occurrence that leaves an impression on someone.”

Oxford Dictionary

Interactions between humans and their environment are the essence of experience. Humans are equipped with a diverse array of sensory apparatus’, the stimulation of which leads to practical contact, observation, knowledge, skill acquisition, events, occurrences, and impressions. Since experience is more than simply the electrical signals generated by the biological sensory apparatus, the sensory apparatus is part and parcel to a larger construal. The individual contributes to the construal himself or herself as the one who construes. The construal takes a contribution from the subject and all of its unique attributes, the object of the stimulus, the stimulus itself, and the internal and external environmental conditions within which the transaction takes place.

Experience is fundamentally subjective and hermeneutical, hence impression. This precludes experience and any decision or judgment made of that experience from being objective and absolute in and of itself.

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

Individual human experience is always of a limited scope. It is limited by our sensory apparatus, what we choose to attend to regarding the information from that sensory apparatus, and our worldview which serves as a filter through which we interpret

Sensory Apparatus Limits

The health of the sense organ itself

The neurological processing system’s health

The accuracy of the sense

Environmental effects on the sense organs

Lack of measurement with a numerical value and units

Previous exposure, or lack thereof, to a set of stimuli

Intrinsic expectations

Availability

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Experiment, Invention, Reason, and Argumentation

2. Memory (Empirical – generating)

Memory, along with experience, serves as a cornerstone to Modern Rational Empiricism. Memory’s influence on thinking and behavior is profound. Given its special status it is necessary to establish a baseline of description and understanding of Memory as a unique element and to contextualize it within Modern Rational Empiricism. As important as memory is to “being” human, and as much as science has done to come to understand it better, there are issues with the reliability of information that comes only from memory. In the search and discovery of truth and facts the information exclusively wrought from Memory represents low quality information when used in critical thinking, decision-making, and making judgments.

“… memory is essential to all aspects of complex cognition …” Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg. x.

“Throughout the book we have encountered memory, and it is indeed hard to imagine an intelligent agent without it. Additionally, learning is a core ability of intelligent systems, and learning is directly coupled to memory.” Rolf, P., Bongard, J., “How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence”, 2007, Pg. 298.

In psychology, Memory (v.) is the biological process in which information from sense experience (visual, auditory, tactile, internal, olfactory, gustatory) is encoded, stored, and retrieved in both implicit and explicit formats. Although the nature of, and the exact mechanism that leads to the generation, processing, and retrieval of Memory is still debated and not yet fully understood as a simple, unified concept, a Memory (n.) is generally described in the literature as a multi-faceted and complex phenomenon developing in three multi-module stages:

“The early outlines of the cognitive system included three kinds of memory stores: sensory input buffers that hold and transform incoming sensory information over a span of a few seconds; a limited short-term working memory where most conscious thinking occurs; and a capacious long-term memory where we store concepts, images, facts, and procedures. These models provided a good account of simple memory achievements, but were limited in their ability to describe more complex inference, judgment, and decision behaviors. Modern conceptions distinguish between several more processing modules and memory buffers, all linked to a central working memory.” Hastie, R., Dawes, Robyn M., “Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making”, 2nd Edition, 2010, Pg. 9.

“Before we continue, a note on terminology is necessary because the word ‘memory’ can mean two things. First, it is the ‘thing’ to be remembered, for example a memory of a wonderful dinner at a girlfriend’s house, the memory of the fish smell in a small port in Okinawa, the memory of taste of an excellent Australian Chardonnay, or the memory of an extremely embarrassing situation. The other meaning is the more abstract, theoretical one; the ‘vehicle,’ so to speak: the set of processes that are responsible for and underlie changes in behavior.” Rolf, P., Bongard, J., “How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence”, 2007, Pg. 300.

In the first stage the raw information (from sensory afferents) must be changed so that it may transition into the neural network to be, for lack of a better word, stored. (The storehouse metaphor, albeit cognitively useful, falls short of being an accurate portrayal of how a memory is contained within the central nervous system). This stage occurs in the back integrative cortex of the brain. The process is termed encoding and allows information from the environment to be created and converted in the form of chemical, electrical, and physical messages.

“Neural networks do not explicitly encode symbolic or propositional knowledge. Instead, they represent knowledge as a pattern of unit activities at a particular point in time. The concept of an activity pattern representing a knowledge state implies that knowledge is stored across the entire network, rather than in a particular node. Knowledge in a connectionist system is therefore referred to as being distributed across the network. For a network to represent distributed knowledge, information must flow through the entire network at all times.” Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg. 86.

“It seems that every fact we know, every idea we understand, and every action we take has the form of a network of neurons in our brain. We know of no other form.” Zull, James E., “The Art of Changing the Brain”, 2002 Pg. 99.

There are two general types of explicit memory encoding: Semantic and Lexical.

“Semantic encoding is the process by which people translate sensory information into a meaningful representation that they perceive, on the basis of their understanding of the meanings of words. In lexical access, they identify words, based on letter combinations, and thereby activate their memory in regard to the words, whereas in semantic encoding, they take the next step and gain access to the meaning of words stored in memory. If people cannot semantically encode the words because meaning of the words do not already exist in memory, they must find another way in which to derive the meanings of the words, such as from noting the context in which they read them.” (MSC author note: Hermeneutically) Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg. 235.

The second stage is signal integration within the neural and chemical network as a form of recording. This creates the place for a Memory in the neural network along a timeline. This allows the possibility that the information can be maintained within the neural network for a period of time. Memory regards the past and can be embedded with strategies like rehearsal.

“Flavell and Wellman (1977) concluded that the major difference between the memory of younger and older children (as well as adults) is not in basic mechanism, but in learned strategies, such as rehearsal.” Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg. 317.

“Experts have a better memory for information that is relevant to their domain of expertise than for information for other domains. Moreover, their memory is attuned to meaningful information. … Chase and Simon concluded that the experts had a different way of organizing knowledge in memory: They were able to remember different board positions by chunking them into meaningful units in memory.” Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg.156.

Finally, the third stage is the retrieval of information – anamnesis – that has been generated and encoded, recorded, and subsequently stored. A Memory can be triggered by some external stimulus or volitionally located and brought to conscious awareness. Volitional reconstruction, recollection, and recall of a Memory may be mentally effortless, or effortful, as a function of the network configuration, and/or the entrenched nature of the memory via conditions, i.e. a traumatic event, or a repetitive stimulus (rehearsal), from which the Memory is encoded and stored.

“Memory for complex events is basically a reconstructive process. As the novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet put it, ‘Memory belongs to the imagination. Human memory is not like a computer which records things; it is part of the imagination process, on the same terms as invention.’ Our recall is organized in ways that make sense of the present. We thus reinforce our belief in the conclusions we have reached about how the past has determined the present. We quite literally make up stories about our lives, the world, and reality in general. The fit between our memories and the stories we make up enhances our belief in them. Often it is the story that creates the memory, rather than vice versa.” Hastie, R., Dawes, Robyn M., “Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making”, 2nd Edition, 2010, Pg. 133.

In Modern Rational Empiricism, Memory plays a fundamental role in thinking by providing content and context to present experience. A Memory is integrated into the existing network and is limited, or potentiated, by the information already contained within the network, as well as how present cognitive process recalls and interprets a Memory within the new context and content within which the memory has been embedded.

One theoretical model of Memory commonly identified within the literature categorizes Memory as: Sensory, Short-term, and Long-term.

Sensory memory: Sensory information is generated and held within the neural and chemical network for periods up to 1 sec after a stimulus is perceived. Sensory memory lies outside of conscious cognitive control and is considered an automatic process.

Short-term memory: Also characterized as “working memory”. Working memory is defined as:

“A portion of memory that contains only the most recently activated knowledge that a person or computational system is attending to at a given time.” Sternberg, Robert J., Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought. 2001, Pg. 382.

“When an intermediate product is stored in a human mind rather than on a disk or on paper, psychologists call it working memory. The two most vivid forms of working memory are mental images also called visuospatial sketchpad, and snatches of inner speech, also called a phonological loop … The fact that language has a physical side – sound and pronunciation – makes it useful as a medium of working memory, because it allows information to be temporarily offloaded into the auditory and motor parts of the brain, freeing up capacity in the central systems that traffic in more abstract information. Pinker, Steven, The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature, 2007, Pg. 129.

Short-term memory occurs in the frontal integrative cortex and allows recall for a period of several seconds to a few minutes without rehearsal and is referred to as the ‘recency effect’. It is characterized as having a very limited capacity. Short-term memory is supported by transient patterns of neuronal communication, dependent on regions of the frontal lobe (especially dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and the parietal lobe. The concept of rote learning, a learning technique that focuses not on understanding but on memorization by means of repetition, provides an example of short-term memory.

“Although maintenance rehearsal (a method of learning through repetition, similar to rote learning) can be useful for memorizing information for a short period of time, studies have shown that elaborative rehearsal, which is a means of relating new material with old information in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the content, is a more efficient means of improving memory. This can be explained by the levels-of-processing model of memory which states that the more in-depth encoding a person undergoes while learning new material by associating it with memories already known to the person, the more likely they are to remember the information later.”

Wikipedia

Long-term memory, on the other hand, is maintained by more stable and permanent changes in neural connections widely spread throughout the brain. The hippocampus is essential to the consolidation of information from short-term to long-term memory, although it does not seem to store information itself. Without the hippocampus, new memories are unable to be stored into long-term memory. Furthermore, the hippocampus may be involved in changing neural connections for a period of three months or more after the initial encoding and storage.

“Long term explicit memories are formed in the hippocampus.” Zull, James E., The Art of Changing the Brain, 2002, Pg. 80.

“But the hippocampus is now known to have a broader function in long-term memory. In fact, it is now thought to be on the route taken by all the information in the surrounding integrative cortex of the back cortex. The current idea is that sensory input, which has been integrated into images, patterns, faces, sounds, and location, all finds its way there. It seems that when information of this sort associated with a particular event or ‘episode’ arrives at the hippocampus, it becomes assembled into an even bigger picture of the episode itself. All the parts of the memory are associated with each other, and it becomes “a memory.” The hippocampus is the master integrator.” Zull, James E., The Art of Changing the Brain, 2002, Pg. 81.

Long-term memory: The storage in sensory memory and short-term memory, generally, has a strictly limited capacity and duration. As such, information is not retained indefinitely within sensory or short-term memory. By contrast, long-term memory can store much larger quantities of information for potentially unlimited durations (sometimes a whole life span). While short-term memory encodes information acoustically, long-term memory encodes it semantically. Baddeley (1966) discovered that, after 20 minutes, test subjects had the most difficulty recalling a collection of words that had similar meanings.

Long Term memory can be divided into two categories: explicit and implicit. Explicit memories are those memories that we are conscious of. Implicit memories are those that we are not conscious of, i.e. feelings, beliefs, and attitudes. Long-term memory is not just extended short-term memory. The two are qualitatively different.

“It is easy to think that memory works like a relay race, where information is passed first to short-term memory and then on to long-term memory. But this is not a very useful metaphor. In fact, working memory and long-term memory involve separate pathways in the brain.” Zull, James E., The Art of Changing the Brain, 2002, Pg. 181.

Episodic, Declarative, and Procedural Memories are all part of long-term memory. Episodic Memory attempts to capture information such as “what” “when” and “where” and can be developed through techniques such as rehearsal. Declarative Memory is dedicated to the representation of factual knowledge. Procedural Memory is dedicated to the representation of knowledge regarding operations and procedures.

“We also know that human thoughts are stored in memory in a form that is far more abstract than sentences. One of the major discoveries in memory research is that people have poor memories for the exact sentences that gave them their knowledge. This amnesia for form, however, does not prevent them from retaining the gist of what they have heard or read… This suggests that stretches of language are ordinarily discarded before they reach memory, and that it is their meanings which are stored, merged into a larger database of conceptual structure.” Pinker, Steven, The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature, 2007, Pg. 149.

“But where is memory, then? Neath and Surprenant: ‘the fundamental question of where memory is located remains unanswered. However, it seems likely that a combination of local and distributed storage will provide the ultimate solution’ (2003). We would add that we may not be asking the right question here: If memory is a theoretical construct rather than a ‘thing,’ the search for it may in fact be futile. What is called memory is about change of behavior, and its underpinnings are not in the brain only. The change of behavior results from changes in brain, body (morphology, materials), and environment. So when we ask, where is memory? We should perhaps be looking not only inside the brain but at specific relationships between the agent, its task, and its environment.” Rolf, P., Bongard, J., “How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence”, 2007, Pg. 321.

The issue of information quality if the information is only from this element:

One’s ability to accurately remember specific details fades quickly over time. Even though one might generate a memory that is the gist of the experience the precision is lost. Combined with the issue of language (that language strongly influences memory and any resulting understanding), if one’s language competency is limited, and/or the intended and interpretive aspects of the language used during an experience are different, then an entirely different memory than the factual aspects of the experience will be constructed. Additionally, emotional and pathological brain states impact accuracy in the creation of a memory and during the recollection of a memory. This can lead to excessively narrow or broad memory information content, and the inaccurate recall of an experience. Memory alone represents an undependable information source in critical thinking, decision-making and making judgments.

“In sum, our memory for perceptually driven details seems to fade at a relatively more rapid pace than does our memory for meaning.” Sternberg, Robert J., “Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought.” 2001, Pg. 60.

“Clearly, language facilities thought, affecting even perception and memory.” Sternberg, Robert J., Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought. 2001, Pg. 219

“Language also affects how we encode, store, and retrieve information in memory in other ways. Loftus (e.g., Loftus & Palmer, 1974) has done extensive work showing that the testimony of eyewitnesses is powerfully influenced by the distinctive phrasing of questions posed to them.” Sternberg, Robert J., Complex Cognition: The Psychology of Human Thought. 2001, Pg. 219

“The principle is simple. When we have experience with a class of phenomena (objects, people, or event), those with a salient characteristic most readily come to mind when we think about that class. It follows that if we estimate the proportion of members of that class who have the distinctive characteristic, we tend to overestimate it … Selective retrieval from memory can produce large misestimates of proportions, leading to a misunderstanding of a serious social problem, and finally to biases in important decisions like those required of voters, jurors, and policy makers.” Hastie, R., Dawes, Robyn M., Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making, 2nd Ed., 2010, Pg. 96-97.

“Moods also affect recall.” Hastie, R., Dawes, Robyn M., Rational Choice in an Uncertain World: The Psychology of Judgment and Decision Making, 2nd Edition, 2010, Pg. 136.

“Our findings demonstrate that affect governs semantic and affective priming within a comparative priming paradigm. The experiments suggest that the effects were due to affective influences on semantic activation. Specifically, the relational processing typical of induced and normatively happy mood is assumed to facilitate the accessibility and the use of semantic concepts, whereas sad moods appear to limit the activation and use of such concepts. Response compatibility may also have contributed to some, but not all, of the results. However, the experiments were not designed specifically to isolate the role of response compatibility processes. In summary, our findings are consistent with theoretical assumptions made by Kuhl (2000), Smith and DeCoster (2000), and Ashby et al., (1999), which suggest that happy moods should maintain, and sad moods should dampen, spreading activation.

These results are consistent with those of other recent studies (e.g., Storbeck & Clore, 2005) in suggesting that many of the basic effects from cognitive psychology disappear or are weakened in negative affective states. Given that respondents are usually in positive moods, these results are consistent with the view that cognition and emotion are intertwined phenomena, and that even basic cognitive processes may have an affective trigger.” Storbeck J., Clore G., The Affective Regulation of Cognitive Priming, Emotion. 2008 Apr; 8(2): 208–215., doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.208

“We tend to think that memories are stored in our brains just as they are in computers. Once registered, the data are put away for safe-keeping and eventual recall. The facts don’t change.

But neuroscientists have shown that each time we remember something, we are reconstructing the event, reassembling it from traces through the brain. Psychologists have pointed out that we also suppress memories that are painful or damaging to self-esteem. We could say that, as a result, memory is unreliable. We could also say it is adaptive, reshaping itself to accommodate the new situations we find ourselves facing. Either way, we have to face the fact that it is ‘flexible’.” Eishold, K., Unreliable Memory: Why Memory’s unreliable and What We Can Do About It., 2012, in Hidden Motive.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Reason, Argumentation, Invention (recording devices), Experiment, Pattern Discernment/Recognition

3. Intuition (Empirical – generating)

Intuition (n.) – The ability to understand something immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning. A thing that one knows or considers likely from instinctive feeling rather than conscious reasoning.

Oxford Dictionary

“What is intuition? Also known as a hunch or gut feeling, it is defined as convincing, hasty feelings whose origins cannot be explained by the individual himself. It comes form the Latin word “intuir”, which means knowledge from within. While you might think of it as being brought about by an internal force, your gut feeling actually starts with a perception of an external factor, say intonation or facial expression so brief that are actually unaware that you have noticed it.” Examined Existence, Intuition, Gut Feeling, and the Brain: Understanding Our Intuition, Dec 11, 2013.

“What is a gut feeling?

A Judgment that …

1. That appears quickly in consciousness

2. Whose underlying reasons we are not fully aware of, and

3. Is strong enough to act upon”

From Gut Feelings by Gerd Gigerenzer, Ph.D.

Gut feelings are built upon the accumulated experiences and memories of one’s life that generates heuristics or “rules of thumb”.

Heuristic (n.) – A rule of thumb, simplification, or educated guess, that reduces or limits the search for solutions in domains that are difficult, complex and/or poorly understood. Unlike algorithms, heuristics do not guarantee optimal, or even feasible, solutions and are often used with no theoretical guarantee; Also – Of, or relating to, a usually speculative formulation serving as a guide in the investigation or solution of a problem.

“Real scientific research of any kind is rooted in value judgments. The list of outstanding scientists in any field would show that these men and women were essentially great artists in the sense that they had the intuitive capacity to ask the right questions in the right way at the right time. Payne, Stanley, L., The Art of Asking Questions, 1980, Pg. x.

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” Albert Einstein

In the thinking framework of Modern Rational Empiricism intuition is taken to mean that an individual at some moment in space-time gains an unmediated insight, understanding, or knowledge of a concept without explanation or knowledge of the source. Intuition is acknowledged as a source of potential input and may represent completely unique content for subsequent thoughtful analysis. However, due to the issues with the limitations of individual experience and the inaccuracy of memory recall information gleaned from intuition is inherently unstable and unreliable.

“There are no authoritative sources of knowledge, and no ‘source’ is particularly reliable. Everything is welcome as a source of inspiration, including ‘intuition’; especially if it suggests new problems to us. But nothing is secure, and we are all fallible.” Popper, Karl R., Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, Revised Edition, pg. 134.

It is interesting that quite often it appears that our intuitions and gut reactions to a set of stimuli in a given context – where a decision is presented – turn out okay, independent of a more thorough and objective analysis (see research by Gerd Gigerenzer). The idea that our subconscious mind can compute, summarize, and conclude information outside of our deliberate conscious thought level often as accurately as a complex, time consuming, and drawn out analysis, is remarkable and should not be discounted. (Sometimes referred to as Tacit Knowledge). The occasional brilliance of our subconscious mind is the knowing, without formalized analytic constructs, which “Rules of Thumb” are likely to apply in a given circumstance. Nature gives each of us capability, extensive experience and practice gives us capacity.

“The primary challenge for human intelligence: to go beyond the information given” Gerd Gigerenzer

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

The problem with information gained from intuition/gut feeling is that if the quality of the accumulated experience is poor and not based on deduction and validity then the quality of the feeling is poor. Intuitively generated information is insecure and could easily have a rival. As well, intuitions/gut feelings are built from individual experiences, which are always limited in scope, and memory. Study after study has shown the significant problems with long-term memory recall accuracy. Intuition is non-discursive and can lack the depth and breadth that discourse may enable through a more thoughtful assessment. Memory lends itself to Association and Availability biases. More information is always better unless the risk of acquiring further data exceeds the perceived benefits.

“Our intuition, particularly intuition influenced and expressed by words, can lead us to be flat-out irrational. Words easily distort reality, which is why writing really good poetry is hard – and an admirable accomplishment – given that feelings as well as external reality are distorted by words.” Dawes, Robyn M., Everyday Irrationality: How pseudo scientists, lunatics, the rest of us systematically fail to think rationally, pg. 28, 2001.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Reason, Argumentation, Invention, Experiment, Association,

4. Association (Rational – processing)

Association is the grouping of events and memories with shared attributes between two or more entities or agents. Association requires and relies on the Associat(or)’s memory (See Memory above) and recollection, or in the case of numerical data the data set. It is an important classifying operation of the mind, connecting language, ideas, concepts, and/or experiences based on temporal relationships.

“In psychology (association) refers to a connection between conceptual entities or mental states that results from the similarity between those states or their proximity in space or time.”

“In statistics, an association is any relationship between two measured quantities that renders them statistically dependent. The term “association” is closely related to the term “correlation.” Both terms imply that two or more variables vary according to some pattern. Wikipedia

“Aristotle put forth four laws of association:

1. The law of contiguity. Things or events that occur close to each other in space or time tend to get linked together in the mind. If you think of a cup, you may think of a saucer; if you think of making coffee, you may then think of drinking that coffee.

- The law of frequency. The more often two things or events are linked in time, the more powerful will be that association. If you have an éclair with your coffee every day, and have done so for the last twenty years, the association will be strong indeed — and you will be fat.

- The law of similarity. If two things are similar, the thought of one will tend to trigger the thought of the other. If you think of one twin, it is hard not to think of the other. If you recollect one birthday, you may find yourself thinking about others as well.

4. The law of contrast. On the other hand, seeing or recalling something may also trigger the recollection of something completely opposite. If you think of the tallest person you know, you may suddenly recall the shortest one as well. If you are thinking about birthdays, the one that was totally different from all the rest is quite likely to come up.” Dr. C. George Boeree

The Systematicity Principle states that connected knowledge is preferred over independent facts. This principle exemplifies the process of Association and its import for cognition. A mnemonic is also an example for the use of mental association between two concepts to improve its cognitive utility. Associations are the mental connections between ideas, things, and pieces of information. Associations are made within temporal periods and information interacting within that period (occurrences). The Associat(or) may use any number of attributes (size, color, function, name, location, etc.) between two or more ideas, things, and pieces of information/data in order to establish a connection or correlation.

How do you evaluate an association claim?

Construct validity – the degree to which a test measures what it claims, or purports, to be measuring.

How well have you measured or remembered each of the two variables in the association?

How was each variable/memory operationalized?

How were the variables/memories measured?

Statistical validity – refers to whether a statistical study is able to draw conclusions that agree with statistical and scientific laws. This means if a conclusion is drawn from a given data set after experimentation, it is said to be scientifically valid if the conclusion drawn from the experiment is scientific and relies on mathematical and statistical laws.

Is the association statistically significant?

What is the effect size?

How strong is the association?

What about Type I and Type II errors?

External validity – the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other situations and to other people or populations.

How is this association generalized to other contexts, times, places, or populations?

How representative and randomized is the sample?

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

Information gleaned only from association is subject to association and representative bias. As well the association may lack context and interpretations derived from the association unfounded.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Experience, Reason, Argumentation, Invention, Experiment, Pattern Discernment, and Memory

5. Pattern Discernment/Recognition/ (Rational – processing)

Pattern (n.) an arrangement or sequence regularly found in comparable objects or events:a regular and intelligible form or sequence discernible in certain actions or situations.

Pattern (v.) give a regular or intelligible form to.

“What is a pattern? How do we come to recognize patterns never seen before? Quantifying the notion of pattern and formalizing the process of pattern discovery go right to the heart of physical science.” James P. Crutchfield, Between order and chaos, Nature Physics 8, 17-24 (January, 2012).

Information from the natural world or man-made – whether gleaned from iconic, auditory, haptic, olfactory, or gustatory stimuli – may be perceived as having some similarity, structure, or order within its images, features, and measurements. Information that portrays, or appears to portray itself with regularity, repetitiveness, or an arrangement may indicate some form of relationship reflecting cause and effect or a correlation. Patterns are initially discerned, whether real or not, by the interpretation of the sensory apparatus as it interacts with an environment and the recalled memory of previous information.

“For inevitably our experience of the natural world is based in the end not directly on behavior that occurs in nature, but rather on the results of our perception and analysis of that behavior.” Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science, pg. 547, 2002.

“Why do people see faces in nature, interpret window stains as human figures, hear voices in random sounds generated by electronic devices or find conspiracies in the daily news? A proximate cause is the priming effect, in which our brain and senses are prepared to interpret stimuli according to an expected model.” Shermer, M., Scientific American, Patternicity: Finding Meaningful Patterns in Meaningless Noise, 11.17.2008.

The Priming Effect, also known as the Priming Paradigm, describes a cognitive process that can be based on the setting up of, or experiencing of, associations between a stimulus and a response within a specific context that influences cognitive process. A circumstance where an individual’s recognition or recollection of a new item can be accelerated by prior exposure to a previous item within a short temporal interval.

“Priming (to prime=to prepare, to instruct in advance) constitutes a cognitive phenomenon that can be predicated on the establishment of context-based associations between a stimulus and a response. Hence, priming and its modes of operation resemble the mechanisms of classical conditioning, wherein a previously presented stimulus (the prime) cues a response as soon as an associated prime (then called target) is presented to the subject at a second test run. By definition, priming originates in an associative link between two events, whereby an event A increases the probability of the occurrence of an event B. The priming effect describes the circumstance that the “prior exposure to a stimulus (prime) can facilitate its subsequent identification and classification (target)”, as the various processing stages that were required to select that response during its first presentation are bypassed.” Clempin C., The Priming Effect and Language Learning

When information is interpreted as being/having/reflecting a pattern this indicates some form of organization. That organization potentially contains inherent rules and related behaviors that enhance one’s understanding of information in an environment. True patterns developed and defined by inherent rules – vs. randomness and chaos – with related behaviors, make it possible to generate predictions, replicate information, and increase the understanding of a phenomenon. Patterns may indicate purpose. This allows for classification and cognitive competency. Patterns are useful processes in human decision-making and the manipulation of said information to some end, i.e. assessing and assigning risk.

“Much is known about how people make decisions under varying levels of probability (risk). Less is known about the neural basis of decision-making when probabilities are uncertain because of missing information (ambiguity). In decision theory, ambiguity about probabilities should not affect choices. Using functional brain imaging, we show that the level of ambiguity in choices correlates positively with activation in the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, and negatively with a striatal system. Moreover, striatal activity correlates positively with expected reward. Neurological subjects with orbitofrontal lesions were insensitive to the level of ambiguity and risk in behavioral choices. These data suggest a general neural circuit responding to degrees of uncertainty, contrary to decision theory.” Hsu M., et al, Neural Systems Responding to Degreed of Freedom in Human Decision-Making, Science, VOl. 310, No. 5754. 09 Dec. 2005, pp. 1680-1683.

In the domain of Statistics, the term pattern is denoted as:

“… the p-dimensional data vector x = (x1 ….., xp)T of measurement (T denotes vector transpose), whose components xi are measurements of the features of an object. Thus the features are the variables specified by the investigator and thought to be important for classification.” Webb, A.R., Statistical Pattern Recognition, pg. 2, 3rd ed. 2011.

In contrast to raw sensory derived information from the natural environment, statistical data sets from numerical measurements and mathematical manipulations are human generated. In formal statistical pattern analysis pattern discernment is the search for, and identifying of, potentially organized behavior and/or structure in a defined information/data field.

“A pattern recognition investigation may consist of several stages enumerated below.

- Formulation of the problem: gaining a clear understanding of the aims of the investigation and planning remaining stages. Data collection: making measurements on appropriate variables and recording details of the data collection procedure (ground math). Initial examination of the data: checking the data, calculating summary statistics and producing plots in order to get a feel for the structure. Feature selection or feature extraction: selecting variables from the measured set that are appropriate for the task. Unsupervised pattern classification or clustering. This may be viewed as exploratory data analysis and it may provide a successful conclusion to a study. On the other hand, it may be a means of preprocessing the data for a supervised classification procedure. Apply and discrimination or regression procedures as appropriate. The classifier is designed using a training set of exemplar patterns. Assessment of results. This may involve applying the training classifier to an independent test set of labeled patterns.Interpretation.” Webb, A.R., Statistical Pattern Recognition, pgs. 3-4, 3rd ed. 2011.

“Computers and rocket ships are examples of invention, not of understanding. … All that is needed to build machines is the knowledge that when one thing happens, another thing happens as a result. It’s an accumulation of simple patterns. A dog can learn patterns. There is no “why & how” in those examples. We don’t understand why electricity travels. We don’t know why light travels at a constant speed forever. All we can do is observe and record patterns.” Scott Adams, God’s Debris: A Thought Experiment, 22, (2004).

Pattern recognition is defined as the connecting of a discerned feature to a remembered one. Pattern recognition aims to classify data (as pattern) based on either a priori knowledge (memory) or on statistical information extracted from the patterns. The patterns to be classified are usually groups of measurements or observational features as defining points in an appropriate multidimensional space.

A complete pattern recognition system consists of a sensor that gathers the observations to be classified or described; a feature extraction mechanism that computes numeric or symbolic information from the observations; and a classification or description scheme that does the actual job of classifying or describing observations, relying on the extracted features.

“The world is, in fact, quite structured, and we now know several of the mechanisms that shape microscopic fluctuations as they are amplified to macroscopic patterns. Critical phenomena in statistical mechanics and pattern formation in dynamics are two arenas that explain in predictive detail how spontaneous organization works. Moreover, everyday experience shows us that nature inherently organizes; it generates pattern. Pattern is as much the fabric of life as life’s unpredictability.” James P. Crutchfield, Between order and chaos, Nature Phys. 8,17–24 (2012); published online 22 December 2011; corrected online 17 May 2013.

The classification or description scheme is usually based on the availability of a set of patterns that have already been classified or described. This set of patterns is termed the training set and the resulting learning strategy is characterized as supervised. Learning can also be unsupervised, in the sense that the system is not given an a priori labeling of patterns, instead it establishes the classes itself based on the statistical regularities of the patterns.

The classification or description scheme usually uses one of the following approaches: statistical (or decision theoretic), syntactic (or structural), or neural. Statistical pattern recognition is based on mathematical characterizations of features constituting a pattern, which assumes that the pattern has been generated by a probabilistic system. Structural pattern recognition is based on the structural interrelationships of features or characteristics within a defined data field. Neural pattern recognition employs the neural computing paradigm that has emerged with increased understanding of biological neural networks.

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

The human sensory apparatus and the subsequent mental processing of information appears to have a strong inclination to identify patterns in the environment – whether a pattern really exists or not – as the human mind is not fond of randomness and chaos. Humans are inclined to impose certainty into circumstances when certainty cannot be ensured. This can lead to apophenia.

Apophenia – the human tendency to perceive meaningful patterns within random data.

“I act with complete certainty. But this certainty is my own.” Ludwig Wittgenstein – On Certainty

“When you can’t predict the outcome of a situation, an alert goes to the brain to pay more attention. A threat response occurs. A 2005 study found that just a little ambiguity on its own lights up the amygdale. The more ambiguity, the more threat response, and the less reward response there was in the ventral striatum. Think about someone you have spoken to a few times by phone, but never met or seen a picture of. You feel a mild uncertainty about them, yet even this tiny uncertainty seems to alter your interactions: notice how differently you interact once you know what that person looks like. Uncertainty is like an inability to create a complete map of a situation. With parts missing, you’re not as comfortable as when the map is complete.” Rock D., A Hunger for Certainty – Your brain craves certainty and avoids uncertainty like pain. Psychology Today, 10.25.09.

Information gleaned only from the recognition or discernment of a pattern is initially inductive and may not lead to an accurate general understanding of causation, or even strong correlation, about some observed phenomenon. Randomness can lead to the perception of a pattern which may mislead one into believing there is some intentional causation or general organizational principle(s) behind the creation of the pattern. The concept of the Priming Effect in cognition can lead to the perception of pattern.

“Through a series of complex formulas that include additional stimuli (wind in the trees) and prior events (past experience with predators and wind), the authors conclude that ‘the inability of individuals—human or otherwise—to assign causal probabilities to all sets of events that occur around them will often force them to lump causal associations with non-causal ones. From here, the evolutionary rationale for superstition is clear: natural selection will favour strategies that make many incorrect causal associations in order to establish those that are essential for survival and reproduction.’” Shermer M., Patternicity: Finding Meaningful Patterns in Meaningless Noise – Why the brain believes something is real when it is not” Scientific American, Dec. 1, 2008

When combining the reality of unconscious cognitive Priming with the natural tendency of humans to impose certainty into circumstances and information, when none is actually present, creates a bias.

In 2008, Michael Shermer coined the word “patternicity”, defining it as “the tendency to find meaningful patterns in meaningless noise.”

In The Believing Brain (2011), Shermer wrote that humans have “the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency”, which he called “agenticity”.

“The phenomenon of priming refers to the behavioral effects of prior exposure to a stimulus, even when explicit memory of the prior experience is not available. The consequences of priming include facilitation in identifying, naming or perceiving an object or word and can also include a tendency for a word to ‘pop into mind’, as in a stem-completion task (for reviews, see Schacter et al., 1993; Roediger and McDermott, 1993). Priming occurs after a single prior presentation of a stimulus, and while the durations of the effects can be fairly transient (e.g. Graf et al., 1984), in some cases effects have been shown to persist for an extended period of time (Cave and Squire, 1992; Cave, 1997). Because priming can produce an increase in perceptual speed (e.g. Feustel et al., 1983; Biederman and Cooper, 1991) or response time performance, it has been proposed to be the first step in the development of automaticity that accompanies expertise (Logan, 1990; Poldrack et al., 1999). The neural correlates of priming have been extensively studied in both neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies (for a review, see Schacter and Buckner, 1998). However, the possible relationship of priming and the development of automaticity and/or perceptual expertise has only begun to be explored with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).” Paul J. Reber, Darren R. Gitelman, Todd B. Parrish, M.-Marsel Mesulam, Priming Effects in the Fusiform Gyrus: Changes in Neural Activity beyond the Second Presentation, Cerebral Cortex June 2005;15:787–795 doi:10.1093/cercor/bhh179 Advance Access publication September 15, 2004.

In conclusion it appears that one of the ways the human mind makes sense of the world is through the associative process of pattern recognition: The goal being to increase predictive power in judgments and decision-making thus reducing uncertainty. Real patterns as defined and described previously are potent cognitive tools. This intrinsic need to be certain and reduce fear has emotional roots in that fear and risk – when defined as a continuum between no certainty and absolute certainty – cohabitate and humans do not desire to live in fear. Quenching this innate need for security can lead to concluding that patterns exist, and the predictive rules that build them, when they really do not. This can create a bias and lead to Type 2 errors and poor decision-making.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Experimentation, Association, Experience, Reason, Argumentation, Memory,

6. Invention (Empirical – processing)

Invention (n.): the action of inventing something, typically a process or device: something, typically a process or device, that has been invented:creative ability:something fabricated or made up. Oxford Dictionary

“… to invent is to discover that we know not, and not to recover or resummon that which we already know.” Sir Francis Bacon

Invention is a creative act. It requires imagination. Humans invent devices, such as telephones. They also invent ideas, such as calculus. Invention often involves the synthesis of pre-existing information and sometimes it is the output of an intuitive de novo “leap”. Cognitively, invention is important in the building of hypotheses, interpretations, and explanations.

“It has been just so in all my inventions. The first step is an intuition – and comes with a burst, then difficulties arise. This thing that gives out and then that -“Bugs” as such little faults and difficulties are called show themselves and months of anxious watching, study and labor are requisite before commercial success—or failure—is certainly reached.”

[Describing his invention of a storage battery that involved 10,296 experiments. Note Edison’s use of the term “Bug” in the engineering research field for a mechanical defect greatly predates the use of the term as applied by Admiral Grace Murray Hopper to a computing defect upon finding a moth in the electronic mainframe.] Thomas Edison Letter to Theodore Puskas (18 Nov 1878). In The Yale Book of Quotations, (2006), 226.

Invention is problem solving and/or innovation. These processes are conjectural by their very nature because forecasted results of the cognitive process cannot reasonably be anticipated or even expected. As well there is no guarantee for the acceptance of a possible result and there is the risk that an accepted result has low utility. Invention needs purpose and direction to transcend from idea or the pure creative expression of art. What’s the problem that needs a solution? What does a solution mean?

“Engineering is quite different from science. Scientists try to understand nature. Engineers try to make things that do not exist in nature. Engineers stress invention. To embody an invention, the engineer must put his idea in concrete terms, and design something that people can use. That something can be a device, a gadget, a material, a method, a computing program, an innovative experiment, a new solution to a problem, or an improvement on what is existing. Since a design has to be concrete, it must have its geometry, dimensions, and characteristic numbers. Almost all engineers working on new designs find that they do not have all the needed information. Most often, they are limited by insufficient scientific knowledge. Thus they study mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology and mechanics. Often they have to add to the sciences relevant to their profession. Thus engineering sciences are born.” Y.C. Fung and P. Tong, Classical and Computational Solid Mechanics (2001), 1.

The issue of information quality if the information is only from this element:

Invention is inductive and conjectural in nature and sometimes serendipitous. Hypotheses as inventions are not necessarily constructed from direct sensory observation and are speculative, thus can inherently lack empirical power.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Reason, Experience, Experiment

7. Experimentation (Empirical – generating)

An individual observes some phenomenon in the natural world, or generates an idea based on cumulative experience in the natural world. That individual asks a question (how? why?) about the observation or idea. That individual may then try to create a tentative explanation, make a prediction, and/or create a perspective regarding the observation or idea – called a hypothesis. How can the individual go about proving or refuting the explanation, prediction, or perspective of the hypothesis? How can they test their hypothesis?

A hypothesis is testable if there is some real hope of deciding whether it is true or false of physical sensory experience. Upon this property rests the ability to decide whether it can be confirmed or falsified by the data of actual experience. A real and actual experience needs to be constructed in some way. This construction is termed experimentation.

Experimentation (n.): The act, process, or practice of experimenting.

Experiment (v.): to perform a scientific procedure, especially in a laboratory, to determine something or try out new ideas or methods.

Experiment (n.): a scientific procedure undertaken to make a discovery, test a hypothesis, or demonstrate a known fact: a course of action tentatively adopted without being sure of the outcome, the collection of research designs which use manipulation and controlled testing to understand causal processes. Generally, one or more variables are manipulated to determine their effect on a dependent variable. Experiments are conducted to be able to predict phenomena.

Scientific Procedure (n.): a step-by-step recipe for a science experiment. A good procedure is detailed and complete allowing others to duplicate the experiment exactly. A.k.a. The Scientific Method(s).

The Scientific Method(s) (n.): The principles and procedures for the systematic pursuit of knowledge involving the recognition and formulation of a problem, the collection of data through observation and experiment, and the formulation and testing of hypotheses. Scientific methods are a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. It is based on gathering observable, empirical, and measurable evidence – data – through experimentation and then subject to specific principles of reasoning.

The Scientific Methods are systematic processes of inquiry. It is exercise in thinking and reasoning, by which a scientist and/or researcher collectively and progressively endeavors to construct an accurate, reliable, consistent, and non-arbitrary representation for observed phenomenon in the world. The effort works to minimize the influence of bias and prejudice on the outcome of the process. It essentially seeks to explain the cause and effect relationships (the how and the why) between the various forms of matter and energy – the variables of interest – in the universe and the results of those interactions.

“What is the broad scope aim of science? To find satisfactory explanations of whatever strikes us as being in need of explanation.” Karl Popper

Categories of Variables manipulated in scientific experiments:

Variable (n.) – an element, feature, or factor that is liable to vary or change.

Independent Variable – The variable that an experimenter changes to test their dependent variable. Purposely manipulated to generate the experimental conditions (i.e., force, resistance, or degrees per second). The effect on the dependent variable is measured and recorded.

Dependent Variable – Observed/recorded to provide information about the effects of the manipulation of the independent variable (i.e., Recorded torque, velocity, range of motion, etc.).

Controlled Variable(s) – Purposely maintained variables at defined conditions so that they do not interfere with the relationships between the independent and dependent variables (e.g., only healthy subjects are tested of the same sex, age, etc.).

Contacting Variable(s) – Variables that can or do interfere with the relationships between independent and dependent variables, (i.e., learning effect, secondary gain issues, environmental conditions, etc.).

General Types of Experiments:

True experimentation: In the strictest sense, experimentation is conducted in such a way that the experimenter manipulates a single variable, and controls or randomizes the remaining variables. Often there is a control group in which the subjects have been randomly assigned between the groups, and the experimenter only tests one effect at a time.

Quasi experimentation: A procedure where the scientist actively influences something to observe the consequences, but the process lacks randomness and/or strict control over the variables.

Typical Designs and Features in Experimentation (Methodologies)

Pretest/Post Test

Check whether the groups are different before the manipulation starts and the effect of the manipulation. Pretests sometimes influence the effect.

Control Group

Control groups are designed to measure research bias and measurement effects. A control group is a group not receiving the same manipulation as the experimental group. Experiments frequently have 2 conditions, but rarely more than 3 conditions at the same time.

Randomized Control Trial

Randomized Sampling, comparison between an Experimental Group and a Control Group and strict control/randomization of all other variables

Solomon Four Group

With two control groups and two experimental groups. Half the groups have a pretest and half do not have a pretest. This is to test both the effect itself and the effect of the pretest.

Between Subjects

Grouping participants to different conditions

Within Subjects (repeated measures)

Participants take part in the different conditions

Counterbalanced Measures

Testing the effect of the order of treatments when no control group is available/ethical

Matched Subjects

Matching experiment participants to create similar Experimental and Control-Groups

Double Blind

Neither the researcher nor the participant, know which is the control group. The results can be affected if the researcher or participants know this.

Bayesian

Using Bayesian probability to “interact” with participants is a more “advanced” experimental design. It can be used for settings where there are many variables which are hard to isolate. The researcher starts with a set of initial beliefs, and tries to adjust them to how participants have responded

In summary, Experimentation is a key element of The Scientific Methods and is a source of the real and actual experience – the data – used to conduct analysis, reach conclusions, and make judgments regarding a hypothesis in question.

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

Information gleaned only from experimentation may lack context. As well, poorly designed and executed true or quasi experiments generate unreliable information. The data collected from experiments needs to be subject to rigorous rational analysis.

“The empirical basis of objective science has thus nothing ‘absolute’ about it. Science does not rest upon rock-bottom. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles. The piles are driven down from above into the swamp, but not down to any natural or given base; and when we cease our attempts to drive our piles into a deeper layer, it is not because we have reached firm ground. We simply stop when we are satisfied that they are firm enough to carry the structure, at least for the time being.” Karl Popper (1959, p. 111)

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Experience, Reason, Argumentation, Association, Pattern Discernment

8. Reason (Rational – processing)

Reason (n.) – A cause, explanation, or justification for an action or event.

Reason (v.) – The set of cognitive tools that are used to draw inferences from what is observed, remembered, and associated. It takes many forms, such as deduction, induction, abduction (analogical), classification, generalization, extrapolation, dialectic, and hypothesis construction. Reasoning.

In this context the verb reason is the focus as this

section is defining and elaborating on the processing,

generating, and interpreting of information relative to Modern Rational

Empiricism. Reasoning as a process has content that is driven by reasons. This

section will describe the basic construct of reasoning processes and its

intention.

Reasoning is used to move from one’s own belief to another by logical inference in domains of uncertainty. Reason always begins with premises and presuppositions (presuppositions may or may not be based in fact or have relevance to the rest of the subject at hand. Therefore, close attention must be paid to the presupposition). Premises and presuppositions are not secure therefore inferences based on them are not secure. Security in this context means that there are still unanswered questions regarding the presuppositions or premises. As well, the acceptance of the influence of bias and error is proactively considered.

Reasoning needs content to process. That content comes about from experience, intuition, and memory. Reasoning attempts to uncover, unpack, and manipulate that content. Its goal as a process is to create an internal congruence and coherence of complex content that is relevant to the reason. The reasoning content-process presents evidence and provides support for claims, decision-making, and judgments. A reasoned process is one of logical justification generating a probability to a claim, judgment, or decision. It clarifies the testability and falsifiability of the reason, the content, and the conclusions.

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

Reasoning requires evidence to balance its conclusions. As well its content could be flawed and its premises and presuppositions insecure.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Experience, Reason, Argumentation, Invention, Experiment, Intuition, Association, Pattern Discernment, and Memory

9. Argumentation (Rational – processing)

Argumentation is a field of studying the reasons and evidence an individual provides to justify their claims, behaviors and/or beliefs and that attempts to influence the thinking and behaviors of an audience. It is primarily focused on the communication processes that seek to persuade people by reasoned judgment, or support decision-making regarding some set of options.

Argumentation is constructed from three areas that intersect and inform each other: Rhetoric, Dialectic and Logic. These are the cognitive vehicles that develop the rationale by which reason is created as process and applied as product. They can take the structure of series, parallel, or convergence in regard to the organization of claims and evidence toward a proposed resolution.

Rhetoric: The study of how messages influence people. Rhetoric focuses on the development and communication of knowledge between speaker and listener. It is reasoning with sensitivity to the audience’s predisposition of mind.

Dialectic: The process of discovering and testing knowledge and its first principles through questions and answers. The process of probing the presuppositions of common sense beliefs as a discourse built on questioning and answering. Socratic dialectic strives to falsify opinions. Platonic dialectic searches for the underlying reality, uninterpretable and axiomatic. Hegelian dialectic is the alleged historical process of ideas through thesis and antithesis moving toward synthesis by building ongoing dialogues and working to achieve consensus – the synthesis. Marxian dialectic views the historical process as material and economic not idea based, that ultimately ends up without an anti-thesis and therefore no more synthesis.

Logic: Both formal (mathematical) and informal (ordinary language) ways of representing the form and structure of reasoning. A system of rules of inference that determine whether or not, (and if so, to what extent) the premises of an argument support its conclusion. Ordinary logic relies on contingent statements that depend on external factors. Modal logic applies notions of possibility and necessity. Predicate logic involves an analysis of the internal structure of subject/predicate sentences i.e. syllogisms and set theory. Sentential logic examines the implications of simple sentences (called unanalyzed units) and truth-functional compound sentences.

Argumentation is the skill of addressing controversies and their uncertainties. The controversy and uncertainty exist because there is not enough absolute factual information; the information may be incomplete or qualitative, meaning that there could be different interpretations and additional explanations. Argumentation is competent persuasion in the face of a potential variety of interpretations and explanations.

The issue of information quality if information is only from this element.

Argumentation may be constructed from insecure suppositions. Argument is pre-constructed with the intention of persuasion and making judgments that may be influenced by biases. Argument inherently lives in the land of uncertainty and its conclusions are subject to multiple interpretations.

Partners/Relationships within the Elements

Reason, Invention, Intuition, Association, Pattern Discernment, and Memory.